|

In the introduction section of the Brittany chapter I wrote:

Sooner or later, if you hunt the prairies long enough, in a truck that’s old enough, you’ll get stuck the middle of nowhere. It happened to me,

last year. After chasing sharptails most of the day under an early-season sun that should have kept me under a shade tree, I found myself in a lifeless pickup truck at the end of a dusty trail in southern Saskatchewan.

My GPS unit showed that the nearest service station was a two-hour hike down the gravel road. With the hot sun sinking near the horizon, I had no choice; I started hiking. After about 20 minutes I heard a vehicle coming up the road from behind. I flagged it down. A friendly farmer—there’s no such thing as an unfriendly farmer in Saskatchewan—leaned out the window.

“Lost?”

“No, my truck won’t start. I think its the alternator.”

“Hop in, I’m on my way to town. Garage is open till 8.”

I climbed into the cab and shared the seat with a white and orange dog wagging a stubby tail. I almost said, “Hey, an Épagneul Breton!” But I remembered that out there on the prairies that’s not the name they go by.

“Nice Brittany,” I said.

“Thanks, he’s getting old. But he still loves to hunt”.

On our way into town the old Brittany held its head in the slipstream and lapped at the wind. I’m sure he was prairie-bred; probably from prairie-bred parents. But I knew his heritage ultimately traced back to little dogs from western France that went on to conquer the hearts of hunters around the world.

Like many of the pointing breeds, the Brittany has a fascinating history. But finding information from the time before the breed was officially recognized in the early 1900s is not easy. Curiously, I've found that there is actually more information available in English than in French about the kinds of pointing dogs that existed in Brittany in the 19th century. Here are some excerpts from the history section of the Brittany chapter:

Like many of the pointing breeds, the Brittany has a fascinating history. But finding information from the time before the breed was officially recognized in the early 1900s is not easy. Curiously, I've found that there is actually more information available in English than in French about the kinds of pointing dogs that existed in Brittany in the 19th century. Here are some excerpts from the history section of the Brittany chapter:Geographically, La Bretagne (“Brittany” in English), is a peninsula in the far west corner of the French hexagon. Culturally, its people have always felt somewhat separate from the rest of the country. Their traditional language, Breton, is not a French dialect, but a Celtic language related to Welsh and Cornish. In fact, until the turn of the 20th century, much of Brittany’s population did not even speak, read or write French. So it is not surprising that very few French texts make any mention of what kind of dogs there were in Brittany before 1900. Fortunately, many of the British sportsmen who travelled to the region in the 1800s wrote articles and published books about their adventures. Recently, many of the old publications have been made available on the internet. Reading through them today, a fascinating picture emerges of what the dogs in Brittany were like in the mid-1800s.

One of the most detailed accounts is from a book titled The Wanderer in Western France written in 1863 by George T. Lowth. In it, Lowth describes short- and long-haired pointing dogs that were “found everywhere” in Brittany:

There is also a breed of setters, quite equal to any in England, and, in fact, not to be distinguished from them. These animals are claimed in Brittany as a native breed, but one cannot help suspecting that it owes its origin, not very many years since, to some of our emigrant countrymen, settled, since the war, in various parts of that country—so tempting to them from its moderate cost of living, and its many advantages in sporting—two irresistible attractions.

English sportsman John Kemp also wrote about his hunting adventures in Brittany and said that it was common practice to cross spaniels and setters.

Another classic book from the same era is Wolf Hunting and Wild Sport in Brittany, written in 1875 by Edward William Lewis Davies who lived in Brittany for two years in the 1850s. He mentions seeing all kinds of dogs: Harriers, Poodles, double-nosed Spanish Pointers, and “mongrels of the lowest type”. He also wrote about a “Brittany Pointer”. This has been interpreted by some as the first mention of the Brittany Spaniel in English. But there are other, earlier descriptions such as the one above, and it is clear that the Brittany Pointer described by Davies had a short coat:

Another classic book from the same era is Wolf Hunting and Wild Sport in Brittany, written in 1875 by Edward William Lewis Davies who lived in Brittany for two years in the 1850s. He mentions seeing all kinds of dogs: Harriers, Poodles, double-nosed Spanish Pointers, and “mongrels of the lowest type”. He also wrote about a “Brittany Pointer”. This has been interpreted by some as the first mention of the Brittany Spaniel in English. But there are other, earlier descriptions such as the one above, and it is clear that the Brittany Pointer described by Davies had a short coat:

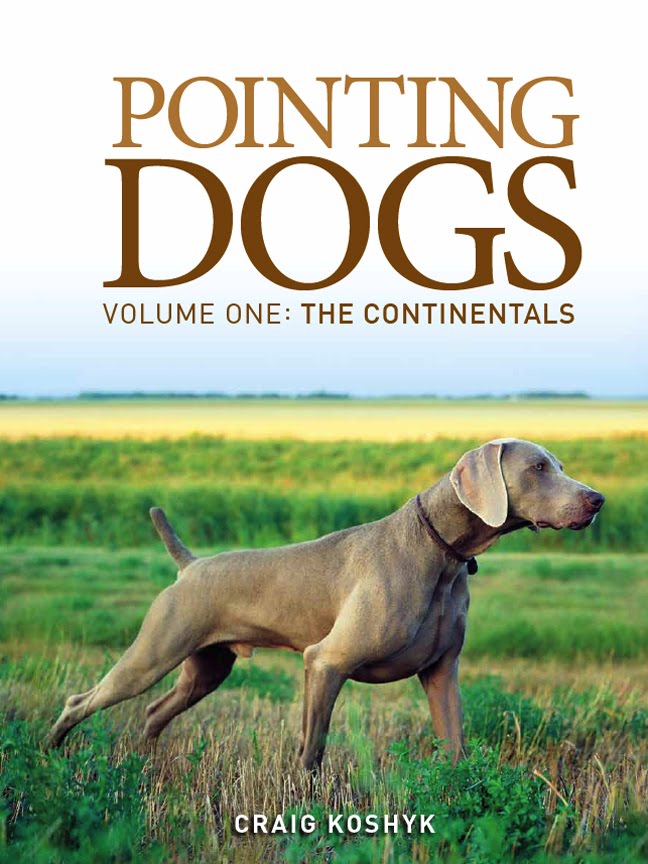

Read more about the breed, and all the other pointing breeds from Continental Europe, in my book Pointing Dogs, Volume One: The Continentals

I have put a spaniel to a well-bred setter bitch, and been lucky enough to combine the ranging qualities of the latter and the hunting perseverance of the former. The French have tried this cross very frequently. I lately purchased one of the produce; and I can say that few dogs perform better in the field than this one

Another classic book from the same era is Wolf Hunting and Wild Sport in Brittany, written in 1875 by Edward William Lewis Davies who lived in Brittany for two years in the 1850s. He mentions seeing all kinds of dogs: Harriers, Poodles, double-nosed Spanish Pointers, and “mongrels of the lowest type”. He also wrote about a “Brittany Pointer”. This has been interpreted by some as the first mention of the Brittany Spaniel in English. But there are other, earlier descriptions such as the one above, and it is clear that the Brittany Pointer described by Davies had a short coat:

Another classic book from the same era is Wolf Hunting and Wild Sport in Brittany, written in 1875 by Edward William Lewis Davies who lived in Brittany for two years in the 1850s. He mentions seeing all kinds of dogs: Harriers, Poodles, double-nosed Spanish Pointers, and “mongrels of the lowest type”. He also wrote about a “Brittany Pointer”. This has been interpreted by some as the first mention of the Brittany Spaniel in English. But there are other, earlier descriptions such as the one above, and it is clear that the Brittany Pointer described by Davies had a short coat: They certainly are not so fine in the skin as the Spanish or English pointers; but, although they do not carry long-haired jackets and feathered stems like setters or spaniels, their coats are thick and close set, and well-adapted to the rough country in which they do their work.However, Davies does write about local hunters cropping the tails of their dogs. Could some of the dogs been naturally short-tailed, a defining characteristic of the first Brittanies?

There is a sad disfigurement practiced on Brittany Pointers...the tail, that indicator of all a dog’s thoughts, that silent tongue that explains all he means, is chopped off in puppyhood by the braconniers (poachers). Yet the poor uneducated peasant of Lower Brittany, the braconnier who gets his livelihood by the chase, shooting partout (everywhere), breaks a pointer for his own use immeasurably superior in many respects to the highly-trained dogs so often met with in our turnip fields and grouse moors. ...he will, as already stated, face the thorniest brake, never rake in drawing for his birds, and, above all, will retrieve his wounded game by land or water perfectly.

Today, the Brittany is known the world over for its "maximum qualities in a minimum volume" and has become the poster-child for the French approach to breeding gundogs.

Read more about the breed, and all the other pointing breeds from Continental Europe, in my book Pointing Dogs, Volume One: The Continentals

Looking forward to reading the blog posts of the various breeds.

ReplyDeleteI think a couple of defining features of this breed are-

Short coupled - a trait that makes then highly manoueverable and fast - like Arab horses. It also gives them a gait unlike other pointing / gundogs - rather clipped. The French have a term - galop.

Très intéressant. J'ai hâte de lire les cinquante autres articles qui vont suivre et en apprendre davantage sur toutes ces belles races de chiens de chasse.

ReplyDeleteLooking forward to your weekly feature. Great start with the loveable Britt.

ReplyDelete